Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was born in Alcalá de Henares, a university town near Madrid, on September 29th 1547, during a period of significant cultural and political transformation in Spain. Born into a family of modest means – his father Rodrigo was an itinerant surgeon of diminished fortunes – Cervantes’ early life was marked by financial instability that would persist throughout his years. Though concrete documentation of his formal education remains sparse, scholars generally believe he studied under the humanist Juan López de Hoyos in Madrid, where he was exposed to Renaissance ideals and classical literature which would later influence his literary perspectives.

The Spain of Cervantes’ youth stood at the apex of its imperial power under Philip II, yet paradoxically faced mounting internal economic pressures and social tensions. This dichotomy between external grandeur and internal strain would later find expression in the dualities that permeate Don Quijote. Cervantes’ formative years coincided with the Counter-Reformation, which reinforced Catholic orthodoxy whilst simultaneously permitting a flourishing of artistic and literary expression now recognized as Spain’s Golden Age (Siglo de Oro).

Military Career and the Battle of Lepanto

In 1570, Cervantes left Spain for Italy, where he entered military service under the command of Don Juan of Austria. This period marked a pivotal transition in his life, exposing him to Italian Renaissance culture and literature – influences that would later manifest in his narrative techniques and literary allusions. On October 7th 1571, Cervantes participated in the Battle of Lepanto, a decisive naval engagement between the Holy League and the Ottoman Empire which halted Ottoman expansion in the Mediterranean. Despite suffering from fever, Cervantes insisted on participating in the battle, where he sustained three gunshot wounds – two to the chest and one that permanently maimed his left hand, earning him the sobriquet “el manco de Lepanto” (the one-handed man of Lepanto).

Cervantes would later regard his participation at Lepanto with immense pride, considering it “the most memorable occasion that past centuries have seen or future generations can hope to witness.” This sentiment reflects not only personal valour but also the profound significance he attached to defending Christendom against Ottoman expansion – a geopolitical conflict which would inform his later literary treatment of Christian-Muslim relations, particularly in his captivity narratives.

Captivity in Algiers

Cervantes’ return journey to Spain in 1575 marked the beginning of another transformative ordeal when the galley El Sol was captured by Barbary corsairs off the Catalan coast. He was taken to Algiers, then under Ottoman control, where he spent five years in captivity. His status as a soldier of some apparent importance, evidenced by letters of recommendation from Don Juan of Austria found on his person, led his captors to demand an exceptionally high ransom of 500 escudos which his family could not readily afford.

During his captivity, Cervantes made four unsuccessful escape attempts, displaying remarkable ingenuity and courage. Rather than receiving the customary severe punishment for these attempts, he was spared by the ruler of Algiers, Hassan Pasha, who reportedly remarked that “so long as the crippled Spaniard was secure, so was Algiers itself secure, as I had no fear for my captives, my vessels, or the entire city.” This period profoundly influenced Cervantes’ worldview and literary imagination, informing his nuanced portrayal of cross-cultural encounters and his complex treatment of freedom, captivity and identity that permeate not only Don Quijote but also his Algiers plays and the “Captive’s Tale” embedded within his masterwork.

Cervantes was finally ransomed by Trinitarian monks in 1580 and returned to Spain, carrying with him experiences that had broadened his cultural horizons whilst deepening his understanding of human resilience in the face of adversity – themes that would become central to his literary oeuvre.

Literary Career and Later Years

Upon his return to Spain, Cervantes found a country transformed by economic challenges despite its continued imperial aspirations. His own financial circumstances remained precarious, compelling him to seek employment as a commissary for the Spanish Armada, procuring supplies for the ill-fated expedition against England. His work as a tax collector in Andalucía led to further misfortunes, including imprisonment in Seville in 1597 due to discrepancies in his accounts – an experience that may have catalyzed the inception of Don Quijote, as tradition suggests he began writing his masterpiece whilst incarcerated.

Cervantes’ literary career began with La Galatea (1585), a pastoral romance which achieved modest success but failed to substantially improve his financial situation. His theatrical works from this period largely disappeared until the rediscovery of Los tratos de Argel and Numancia in the 18th century, plays that draw upon his experiences in captivity and his engagement with classical themes respectively. However, his literary aspirations faced significant challenges in a theatrical landscape dominated by Lope de Vega, whose prolific output and new dramatic formula, the comedia nueva, revolutionized Spanish theatre.

It was not until the publication of the first part of Don Quijote in 1605, when Cervantes was 58 years old, that he achieved literary recognition commensurate with his genius. The novel’s immediate success throughout Europe transformed his literary fortunes, though his financial circumstances remained modest. Spurred by this success and by the appearance of an unauthorized continuation of Don Quijote by Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda in 1614, Cervantes completed his own second part in 1615, a work of greater philosophical depth and narrative sophistication than its predecessor.

In his final years, Cervantes experienced a remarkable creative flourishing, publishing his Novelas ejemplares (Exemplary Novels) in 1613, Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus) in 1614 and completing Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (The Trials of Persiles and Sigismunda), published posthumously in 1617. Despite failing health, he maintained his characteristic wit and philosophical equanimity, famously writing in the prologue to Persiles, completed just days before his death: “Farewell, humours; farewell, jests; farewell, merry friends; for I am dying and wish to have nothing to do but with death, which I hope is coming so quickly there will be no time to publicize my disillusionment.”

Cervantes died on April 22nd 1616 (coincidentally within a day of Shakespeare’s death) and was buried in the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians in Madrid – a fitting resting place given the order’s role in securing his freedom from captivity decades earlier. Though he died without witnessing the full extent of his literary legacy, he had succeeded in creating a work that would transform world literature and secure his place among its greatest practitioners.

The Genesis and Context of Don Quijote

Literary and Cultural Milieu of Golden Age Spain

Don Quijote emerged from a specific literary and cultural context that profoundly shaped its conception and reception. By the late sixteenth century, Spain had developed a rich and varied literary tradition influenced by both indigenous developments and imported forms. The chivalric romance, exemplified by Amadís de Gaula and its numerous imitators, had enjoyed immense popularity throughout the sixteenth century despite periodic condemnation by moralists and intellectuals who criticized these works for their fantastical elements and potentially corrupting influence on readers.

The Spanish literary landscape also encompassed pastoral romances (influenced by Italian models), the picaresque tradition (inaugurated by the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes in 1554), sentimental novels, Byzantine romances and a flourishing theatrical culture. This diverse literary environment provided Cervantes with multiple generic conventions to appropriate, subvert and transform in his creation of a new narrative form.

Contemporaneously, Spain was experiencing significant socio-economic tensions despite its apparent imperial zenith. The influx of American silver had triggered inflation and economic instability, whilst the maintenance of Spain’s European hegemony strained national resources. The hidalgo class—the lower nobility to which Don Quijote belongs—faced particular challenges, struggling to maintain aristocratic pretensions amid diminishing economic means. Cervantes, acutely aware of these social contradictions, incorporated them into his narrative, creating in Don Quijote a figure whose anachronistic ideals and aspirations reflect broader tensions between traditional values and changing social realities.

Cervantes’ Literary Innovations and the Birth of the Novel

Cervantes’ approach to narrative represents a profound departure from preceding literary forms. whilst Don Quijote initially presents itself as a parody of chivalric romances, it rapidly transcends this limited ambition to become something entirely new—what literary historians now recognize as the first modern novel. This innovation manifests in several crucial aspects:

- Psychological Depth and Character Development: Unlike the static, archetypal figures of earlier prose forms, Cervantes’ characters possess psychological complexity and evolve throughout the narrative. Don Quijote and Sancho Panza, in particular, demonstrate remarkable development—the former occasionally glimpsing reality through his delusions, the latter increasingly absorbing elements of his master’s idealism without abandoning his pragmatic worldview.

- Realism and Verisimilitude: Cervantes grounds his narrative in the concrete social and physical reality of late sixteenth-century Spain, describing ordinary locations, common people and everyday occurrences with unprecedented specificity. This commitment to verisimilitude serves not to eliminate the fantastic but to create a productive tension between the real and the imagined.

- Narrative Complexity: The novel employs multiple narrators and narrative levels, beginning with the initial unnamed narrator, transitioning to the purported Arab historian Cide Hamete Benengeli and incorporating the perspective of the morisco translator. This complex narrative structure destabilizes authority and invites readers to actively interpret rather than passively consume the text.

- Meta-literary Awareness: Perhaps most innovatively, Don Quijote demonstrates acute self-consciousness about its status as a literary artifact. In Part Two, characters have read Part One and interact with Don Quijote based on their knowledge of his textual representation. This radical metafictional turn anticipates postmodern literary techniques by several centuries.

- Genre Hybridization: Cervantes incorporates elements from multiple literary traditions—picaresque episodes, pastoral interludes, novella-like interpolated tales, philosophical dialogues—creating a textual heteroglossia that reflects the diversity of human experience itself.

These innovations collectively constituted a new literary form that transcended existing generic boundaries. whilst drawing on traditional material, Cervantes fundamentally transformed it through his psychological insight, narrative sophistication and philosophical depth, establishing a template for novelistic development that would influence centuries of subsequent literary production.

Publication History and Contemporary Reception

The first part of Don Quijote, published by Francisco de Robles in Madrid in January 1605 under the title El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha, achieved immediate and widespread success. The initial print run of 400 copies quickly sold out, necessitating multiple reprints within the first year. The novel’s popularity extended beyond Spain, with translations appearing in English (Thomas Shelton, 1612) and French (César Oudin, 1614) within a decade of its original publication.

This success prompted an unauthorized continuation by Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda in 1614, published under the title Segundo tomo del ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha. Avellaneda’s continuation not only appropriated Cervantes’ characters but also included a preface attacking the original author—provocation that galvanized Cervantes to complete his own second part. Published in 1615 as Segunda parte del ingenioso caballero don Quijote de la Mancha, Cervantes’ continuation explicitly acknowledges and responds to Avellaneda’s version, incorporating this literary usurpation into the narrative itself.

Contemporary reception of Don Quijote initially focused on its comedic elements, with many readers viewing it primarily as an entertaining satire of chivalric literature. However, even early readers recognized the work’s unusual depth, with the Spanish humanist Márquez Torres noting in 1615 that French courtiers praised the novel for “the decorum with which [Cervantes] treats Don Quijote, though he is a madman and the preservation of his esteem despite his follies.” This observation suggests an emerging recognition of the novel’s complex balance between comedy and seriousness, mockery and empathy.

The reception history of Don Quijote would evolve significantly over subsequent centuries, with interpretations ranging from simplistic readings as mere comedy to profoundly philosophical approaches emphasizing existential themes. This interpretive multiplicity reflects not only changing cultural contexts but also the genuine ambiguity and richness that Cervantes embedded in his text—qualities that have ensured its enduring relevance across vastly different historical periods.

Textual Analysis and Interpretation

Narrative Structure and Technique

Don Quijote employs a narrative architecture of remarkable sophistication, especially considering its pioneering status in the development of the novel form. The work’s structural complexity operates on multiple levels:

At the broadest level, the bipartite division between the 1605 and 1615 publications creates significant narratological differences. Part One follows a more episodic structure with numerous interpolated tales somewhat tangentially related to the main narrative. By contrast, Part Two demonstrates greater cohesion and purposefulness, with the protagonists’ adventures more integrally connected to their psychological development and the novel’s thematic concerns.

Within this larger framework, Cervantes constructs an elaborate system of narrative mediation that undermines any pretense to authoritative discourse. The initial narrator presents himself merely as a compiler of existing accounts, attributing the authoritative version to the Arab historian Cide Hamete Benengeli, whose manuscript requires translation by an unnamed morisco. This layered attribution creates deliberate ambiguity about textual authenticity, further complicated by occasional editorial interventions where the narrator comments on Benengeli’s reliability or the quality of the translation.

This complex narrative apparatus serves multiple functions. It creates ironic distance between the events narrated and their representation, enabling commentary on the process of storytelling itself. It also introduces cultural and religious difference into the very mechanism of narration, as the story of the Christian knight is mediated through Muslim historiography and translation—a striking choice given the historical tensions between Christianity and Islam in early modern Spain. Moreover, it anticipates modern concerns about textual instability and the constructed nature of historical accounts.

Cervantes’ handling of time and space similarly demonstrates remarkable innovation. whilst maintaining a broadly linear chronology, the novel employs various temporal manipulations, including acceleration, deceleration, ellipsis and retrospection. The geography of the novel—primarily La Mancha, but extending to Barcelona in Part Two—combines precisely realized locations with deliberately vague spaces, creating a landscape that is simultaneously concrete and mythic.

Perhaps most revolutionary is the novel’s metafictional dimension, particularly in Part Two, where characters have read Part One and interact with Don Quijote based on their knowledge of his textual representation. This self-reflexivity reaches its apex when Don Quijote and Sancho encounter a character with a copy of Avellaneda’s spurious continuation, thereby incorporating the actual circumstances of publication into the fictional world. This collapse of boundaries between text and world, fiction and reality, anticipates postmodern literary techniques by several centuries and fundamentally challenges conventional understandings of mimesis.

Thematic Complexity

Beyond its narrative innovations, Don Quijote explores a range of profound themes that have ensured its continued relevance across vastly different historical and cultural contexts:

The Relationship Between Fiction and Reality: At its core, Don Quijote examines how literature shapes perception and how imagination transforms experience. Don Quijote’s “madness” consists precisely in his inability to distinguish between literary conventions and empirical reality—yet the novel repeatedly suggests that his “enchanted” vision sometimes penetrates to deeper truths than the supposedly objective perspectives of other characters. This dialectic between illusion and reality extends beyond the protagonist to implicate readers themselves, who must navigate between different levels of fictionality and competing claims to truth.

Identity and Self-Creation: The novel presents identity as performative and contingent rather than essential and fixed. Don Quijote’s transformation from Alonso Quijano into a knight-errant represents a radical act of self-invention, whilst Sancho’s gradual “quixotization” demonstrates how identity evolves through social interaction and narrative participation. Significantly, other characters frequently adopt disguises or play roles, suggesting that all identity involves elements of performance and self-narration.

Social Critique and Class Dynamics: whilst avoiding simplistic political messaging, Don Quijote offers nuanced commentary on early modern Spanish society. The relationship between Don Quijote and Sancho illuminates class tensions whilst ultimately transcending them through genuine friendship. Episodes involving Duke and Duchess in Part Two provide particularly pointed satire of aristocratic privilege and cruelty, whilst interactions with various marginalized figures—galley slaves, moriscos, prostitutes—often challenge conventional moral hierarchies.

Freedom and Constraint: Drawing on Cervantes’ personal experience of captivity, the novel repeatedly examines physical and psychological forms of freedom and imprisonment. Don Quijote’s famous declaration “Freedom, Sancho, is one of the most precious gifts heaven gave to men” resonates throughout a narrative where characters continually negotiate various constraints—social, economic, religious and interpersonal.

The Nature of Wisdom and Folly: The novel systematically undermines simplistic distinctions between wisdom and madness. Don Quijote’s “insanity” coexists with eloquent rationality on subjects outside chivalry, whilst ostensibly “sane” characters often demonstrate moral blindness or cruelty. Similarly, Sancho’s apparent simplicity frequently reveals profound insight, particularly through his proverbial wisdom. This dialectic culminates in Quijote’s deathbed renunciation of chivalric literature, which simultaneously represents a return to conventional reason and the abandonment of idealistic vision.

Literary Theory and Criticism: Throughout the novel, Cervantes engages in sophisticated literary criticism, evaluating genres ranging from chivalric romance to pastoral poetry, establishing criteria for literary quality and reflecting on the social functions and ethical implications of fiction. The Canonical’s discourse in Part One and conversations with the Knight of the Green Coat in Part Two offer particularly explicit literary-critical content, but the entire novel functions as an extended meditation on how literature shapes both individual consciousness and collective culture.

These thematic concerns, addressed with remarkable subtlety and without didacticism, contribute to the novel’s enduring appeal across cultural boundaries and historical periods. Cervantes’ ability to engage profound philosophical questions whilst maintaining narrative vitality and humor represents one of his most significant achievements.

Character Development and Psychological Insight

Cervantes’ approach to characterization represents one of his most significant innovations. Unlike the static, archetypal figures of chivalric romances, Don Quijote presents characters of psychological depth who evolve throughout the narrative:

Don Quijote: whilst initially presented as a one-dimensional parody of the chivalric hero, Don Quijote rapidly emerges as a figure of extraordinary complexity. His madness operates selectively, leaving him articulate and reasonable on subjects outside chivalry. Throughout the narrative, he experiences moments of lucidity that complicate any simplistic understanding of his delusion. His evolution is particularly notable in Part Two, where he demonstrates greater self-awareness and occasionally questions his chivalric vision. His death-bed renunciation of chivalric literature represents the culmination of this development, though Cervantes leaves ambiguous whether this represents genuine insight or the final tragedy of a noble idealist.

Sancho Panza: Perhaps the most remarkable character development occurs in Sancho, who transforms from a simple, materially motivated peasant into a figure of surprising wisdom and emotional depth. whilst initially skeptical of his master’s delusions, Sancho gradually absorbs elements of Quixotic idealism without abandoning his fundamental pragmatism—a process scholars have termed “Quixotization.” This development culminates in his governorship of Barataria, where he demonstrates unexpected judicial wisdom and in his attempts to re-enchant a disillusioned Don Quijote in the novel’s final chapters.

Secondary Characters: Even minor figures receive nuanced treatment that defies one-dimensional characterization. Dorothea demonstrates both vulnerability and agency in navigating her complex social position. The priest and barber, despite their ostensible concern for Don Quijote’s welfare, frequently exploit his delusions for entertainment. The Duke and Duchess exhibit casual cruelty beneath aristocratic refinement. This consistent psychological complexity extends the novel’s realism beyond physical verisimilitude to encompass the contradictions and ambiguities of human motivation.

Cervantes’ psychological insight is particularly evident in his treatment of intersubjectivity—how characters perceive and influence each other. The evolving relationship between Don Quijote and Sancho transcends its initial master-servant dynamic to become a profound friendship characterized by mutual influence. Similarly, other characters’ reactions to Don Quijote range from mockery to fascination to grudging respect, suggesting the complexities of social perception and the fundamental unknowability of others.

This psychological depth represents a decisive break from earlier narrative forms and establishes a precedent for the novel’s characteristic focus on interior life and interpersonal dynamics. By creating characters who transcend literary types to approximate the complexity of actual human beings, Cervantes established psychological realism as a defining feature of novelistic discourse.

Literary and Cultural Legacy

Influence on Literary Development

Don Quijote‘s impact on subsequent literary production has been so profound and pervasive that virtually all novelistic tradition acknowledges its foundational status, either explicitly through direct allusion or implicitly through inherited formal and thematic concerns.

In the eighteenth century, seminal English novelists consciously positioned themselves in relation to Cervantes’ precedent. Henry Fielding explicitly identified Joseph Andrews (1742) as written “in the manner of Cervantes,” whilst Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759-67) adopted and expanded Cervantine metafictional techniques. In Germany, Christoph Martin Wieland’s Don Silvio de Rosalva (1764) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1795-96) demonstrate significant Cervantine influence, particularly in their treatment of literary idealism and its collision with social reality.

The nineteenth century witnessed diverse appropriations of Cervantes’ legacy. Romantic interpretations, exemplified by Friedrich Schlegel and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, emphasized Don Quijote as a profound meditation on the human condition rather than mere satire. This reading influenced Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (1869), which reimagines Don Quijote’s idealism in a Christian context. Meanwhilst, realist novelists like Gustave Flaubert (Madame Bovary, 1857) and Benito Pérez Galdós (the “Novelas contemporáneas”) adapted Cervantine techniques to critique modern delusions and social contradictions.

Modernist and postmodernist writers further expanded Cervantes’ legacy. James Joyce acknowledged Don Quijote as an influence on Ulysses (1922), particularly in its episodic structure and stylistic experimentation. Jorge Luis Borges repeatedly engaged with Cervantes in both fiction and essays, most notably in “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quijote” (1939), which radically explores questions of authorship and interpretation. Postmodern novels such as John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse (1968), Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler (1979) and Paul Auster’s City of Glass (1985) develop Cervantine metafiction in increasingly complex ways, reflecting on the relationship between narrative and reality.

Beyond these specific examples, Don Quijote has contributed fundamental concepts to literary discourse: the problematic hero whose idealism collides with social reality; the dialectic between romance and realism; the self-conscious narrative that comments on its own conventions; and the complex relationship between author, text and reader. These innovations have become so thoroughly integrated into novelistic tradition that they constitute part of its genetic material, often influencing writers who may not have engaged directly with Cervantes’ text.

Cultural Impact Beyond Literature

Don Quijote‘s influence extends far beyond literary production to permeate broader cultural discourse across multiple media and intellectual domains:

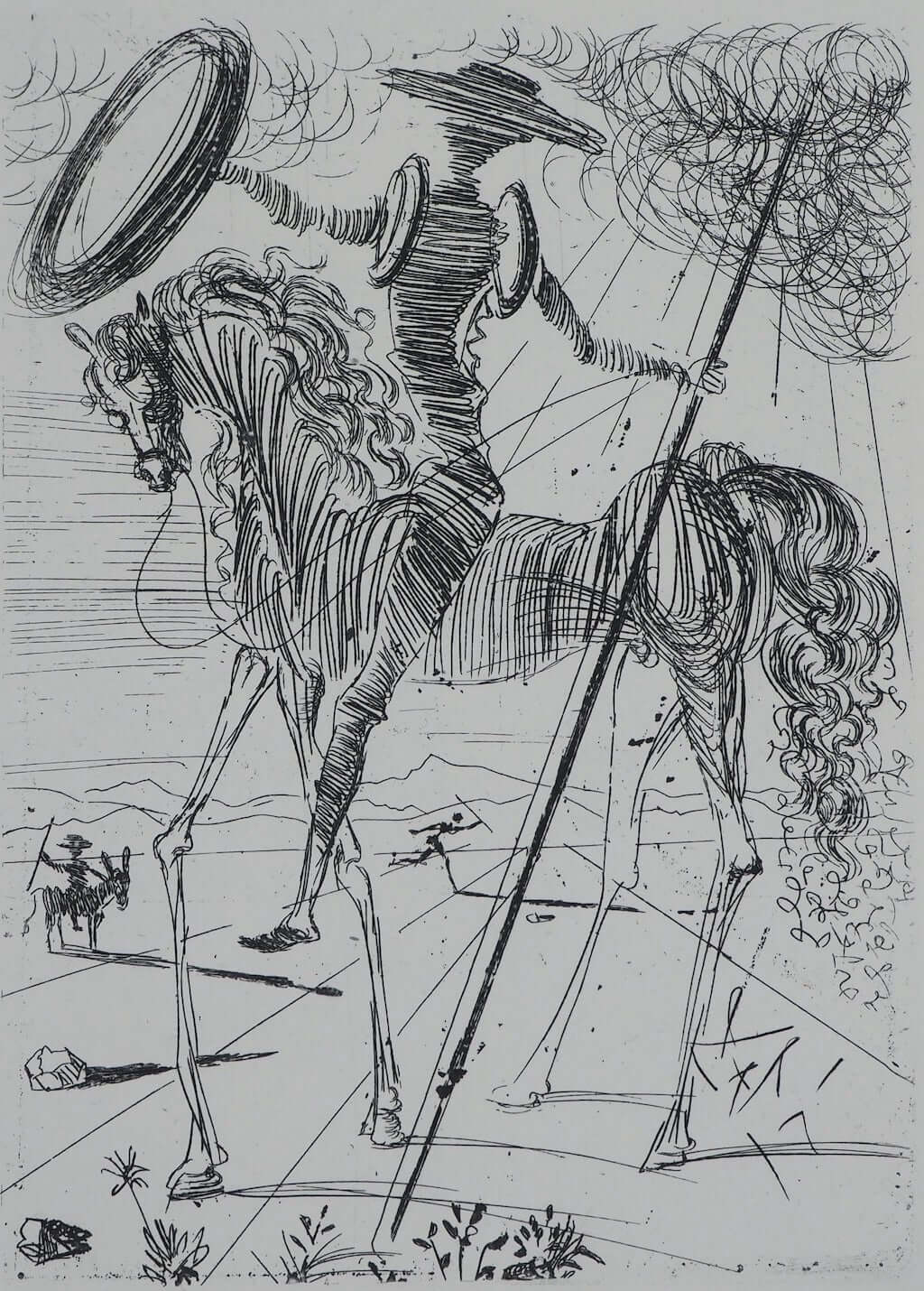

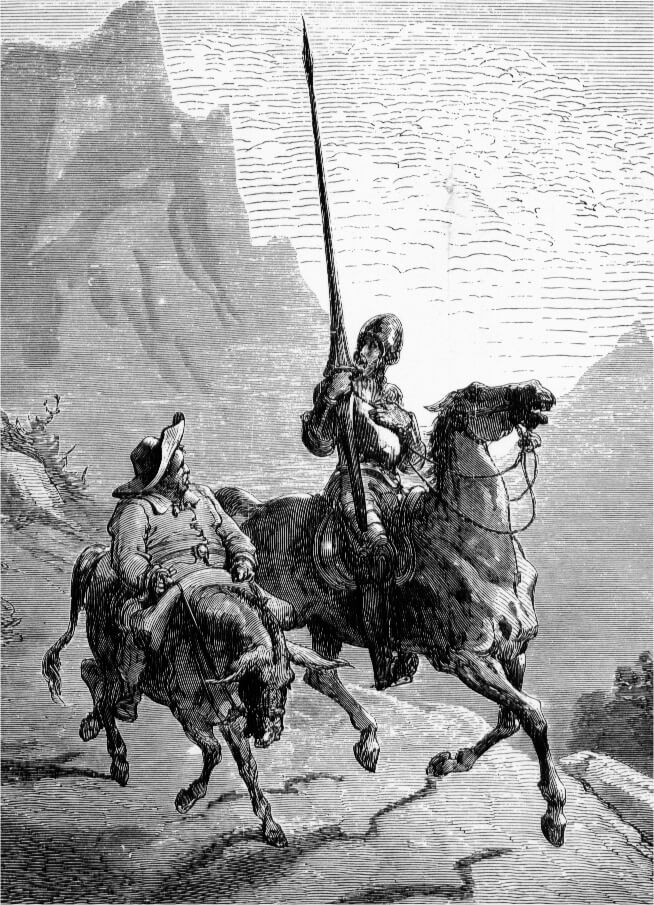

In visual arts, the novel has inspired countless interpretations, beginning with early illustrated editions and continuing through major artistic engagements by Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. These visual representations have themselves contributed to the novel’s cultural dissemination, with certain images—particularly Don Quijote tilting at windmills—achieving iconic status recognizable even to those who have not read the text.

Musical adaptations range from instrumental works like Richard Strauss’s symphonic poem Don Quijote (1897) to operas such as Jules Massenet’s Don Quichotte (1910) and ballets like Marius Petipa’s choreography for Ludwig Minkus’s Don Quijote (1869). These diverse interpretations emphasize different aspects of Cervantes’ text—heroism, comedy, tragedy, romance—demonstrating the novel’s remarkable adaptability to various aesthetic frameworks.

Cinematically, Don Quijote has generated numerous adaptations, including G.W. Pabst’s 1933 film starring Feodor Chaliapin, Rafael Gil’s 1947 Spanish production and Terry Gilliam’s notoriously troubled production The Man Who Killed Don Quijote (finally completed in 2018). Orson Welles’s unfinished Don Quijote project (1955-1972) has itself acquired legendary status, becoming a meta-Quixotic endeavor whose ambition exceeded practical constraints.

Philosophically, the novel has stimulated diverse interpretations. Miguel de Unamuno’s The Life of Don Quijote and Sancho (1905) reads Cervantes’ characters as exemplars of Spanish national character and existential authenticity. José Ortega y Gasset’s Meditations on Quijote (1914) uses the novel to explore the relationship between Mediterranean impression and Germanic concept. Poststructuralist approaches, exemplified by Michel Foucault’s discussion in The Order of Things (1966), emphasize the novel’s epistemological implications and its relationship to changing systems of knowledge.

In popular discourse, the figure of Don Quijote has generated enduring idioms and conceptual frameworks. “Tilting at windmills” signifies misguided idealism, whilst “quixotic” describes impractical pursuit of lofty goals. These linguistic traces demonstrate how thoroughly Cervantes’ creation has permeated cultural consciousness, providing archetypal patterns for understanding the relationship between idealism and reality, imagination and social constraint.

Contemporary Relevance and Ongoing Scholarly Debates

Don Quijote maintains remarkable contemporary relevance through its engagement with perennial human concerns and its anticipation of specifically modern preoccupations. Its exploration of how fiction shapes reality resonates powerfully in our media-saturated age, whilst its treatment of identity as performative rather than essential aligns with contemporary theoretical approaches. The novel’s simultaneous engagement with and critique of globalization—presented through the international circulation of chivalric romances and the encounters between Christian and Muslim cultures—speaks to current anxieties about cultural exchange and conflict.

Scholarly approaches to Don Quijote continue to evolve, generating productive interpretive debates. Traditional philological approaches coexist with newer theoretical methodologies, including:

New Historicist readings situate the novel within early modern Spanish culture, examining its relationship to imperial ideology, economic transformations and religious conflicts, particularly regarding moriscos (Muslims nominally converted to Christianity) and conversos (Jews similarly converted).

Feminist and gender-focused approaches analyze the novel’s treatment of masculine identity, female agency and sexuality, noting both the constraints imposed on female characters and the surprising spaces for resistance they nevertheless navigate.

Postcolonial interpretations examine Don Quijote in relation to Spain’s imperial project, noting its complex engagement with cultural difference and its ambivalent treatment of conquest narratives.

Cognitive and psychological readings employ modern understanding of mental processes to illuminate Cervantes’ remarkable insights into human perception, memory and identity formation.

These diverse approaches testify to the novel’s inexhaustible interpretive richness and its capacity to generate new meanings across changing historical and cultural contexts. As Carlos Fuentes observed, Don Quijote is “an open book” that “breathes as it is read, because the reading of the Quijote is, in effect, its writing.”

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Cervantes and Don Quijote

Four centuries after its publication, Don Quijote remains a work of extraordinary vitality and relevance, continuing to generate new readings and to influence literary production across cultural boundaries. This endurance stems not merely from historical primacy—its status as “the first modern novel”—but from the profound human truths it articulates through its innovative form.

Cervantes’ achievement lies in creating a narrative that simultaneously entertains and philosophizes, that balances comedy with tragedy, cynicism with idealism. The novel’s remarkable tonal range—from slapstick humor to profound meditation—allows it to encompass the full spectrum of human experience, resisting reductive interpretation whilst inviting continuous engagement.

Beyond specific thematic concerns or formal innovations, Don Quijote‘s greatest legacy may be its fundamentally generous vision of humanity. Despite unflinchingly depicting cruelty, hypocrisy and delusion, the novel ultimately affirms human dignity and the transformative power of imagination. In Don Quijote’s capacity to envision a more noble world than the one he inhabits and in Sancho’s gradual embracing of that vision whilst maintaining his connection to material reality, Cervantes offers a model of how idealism and pragmatism might productively coexist.

This ethical dimension ensures that Don Quijote transcends mere literary or historical interest to address fundamental questions about how to live meaningfully in an imperfect world—questions that retain their urgency across vastly different cultural and historical contexts. As Milan Kundera observed, the novel form itself, inaugurated by Cervantes, represents “the great art of the European modern age,” characterized by its ambiguity, complexity and resistance to ideological certainty.

In this sense, Don Quijote not only established a new literary form but articulated a distinctively modern consciousness—one that acknowledges the provisionality of knowledge, the complexity of human motivation and the power of narrative to shape reality. That this consciousness remains recognizably our own, despite vast historical changes, testifies to Cervantes’ profound insight into the human condition and ensures his masterpiece’s continued relevance in our contemporary world.

FAQs about Don Quijote

What is Don Quijote about?

The novel follows Alonso Quixano, an aging gentleman who, after reading too many chivalric romances, loses his sanity and decides to become a knight-errant under the name Don Quijote. Accompanied by his squire Sancho Panza, he sets out on various adventures, often mistaking ordinary objects for magical or extraordinary things. Throughout their journey, Don Quijote’s idealistic worldview repeatedly clashes with reality, creating both comedic and profound moments that explore the nature of perception, identity and the transformative power of literature. The novel functions simultaneously as a parody of chivalric romances and a complex philosophical examination of how stories shape our understanding of the world.

Why is Don Quijote considered the first modern novel?

Don Quijote revolutionized literature by introducing psychological depth and complexity previously unseen in fictional narratives. Cervantes broke with traditional storytelling by creating characters who evolve throughout the story, employing multiple narrative perspectives and using metafictional techniques that draw attention to the book’s status as a constructed text. The novel also uniquely combines various literary genres and registers, from high-minded philosophical discourse to colloquial dialogue, whilst consistently questioning the relationship between fiction and reality. This self-awareness about its own fictional nature, combined with its exploration of human psychology and identity, established the foundation for what would become the modern novel.

What’s the difference between Part One (1605) and Part Two (1615)?

The two parts of Don Quijote reflect Cervantes’ evolving artistic vision and response to his novel’s unexpected success. Part One follows a more episodic structure heavily focused on parodying chivalric romances, with numerous interpolated tales only loosely connected to the main narrative. Part Two, written a decade later, demonstrates greater narrative cohesion and psychological complexity, notably addressing its own reception by having characters who have read Part One and recognize Don Quijote. This metafictional turn allows Cervantes to explore themes of fame, authorship and identity in deeper ways, whilst also showing more nuanced character development, particularly in Sancho Panza, who grows from a simple peasant into a figure of surprising wisdom.

What are the main themes of the novel?

Don Quijote explores the complex interplay between fiction and reality as its central concern, examining how stories shape our perception and how imagination can transform ordinary experience. The novel delves into questions of personal identity and self-invention, suggesting that we become what we pretend to be, whilst simultaneously exploring social hierarchies in Spanish society through the knight-squire relationship. Cervantes balances idealism against pragmatism, suggesting that both perspectives have value and limitations. Throughout the work, the nature of madness and wisdom is constantly questioned, with the supposedly insane protagonist often revealing profound insights whilst “rational” characters demonstrate various forms of folly. The text also meditates on friendship, loyalty and the human capacity for compassion and growth through its central relationships.

How does Cervantes use different narrative techniques?

Cervantes employs a sophisticated array of narrative strategies that were revolutionary for his time and continue to influence literature today. He constructs a complex framing device featuring multiple narrators—including the supposed Arabic historian Cide Hamete Benengeli, an unnamed translator and Cervantes himself as editor—creating layers of unreliability that force readers to question textual authority. The novel shifts between narrative voices and perspectives, sometimes mid-chapter, whilst incorporating diverse genres from pastoral romance to picaresque tales. Perhaps most innovatively, Cervantes develops metafictional commentary throughout Part Two, where characters discuss the first part’s publication and their own fictional status. This self-consciousness about storytelling, combined with the blending of comedy and philosophy, established narrative techniques that would become hallmarks of the modern novel.

What is the significance of Sancho Panza?

Sancho Panza functions as much more than a comic sidekick; he represents one of literature’s most fully realized character transformations. Initially motivated by promises of material reward, Sancho gradually internalizes aspects of Don Quijote’s idealism whilst retaining his practical nature, creating a unique worldview sometimes called “Sanchification.” His earthy wisdom, expressed through an endless supply of proverbs, provides a counterpoint to Don Quijote’s bookish knowledge. As the narrative progresses, particularly in Part Two, Sancho demonstrates unexpected depths during his governorship of Barataria, where his natural justice and common sense triumph over educated foolishness. The evolving relationship between knight and squire—moving from master-servant to a genuine friendship based on mutual respect—forms the emotional heart of the novel and illustrates Cervantes’ humanistic vision.

What was happening in Spain when Cervantes wrote Don Quijote?

Cervantes wrote Don Quijote during a period of profound transition in Spanish society, as the country’s “Golden Age” of imperial expansion began giving way to economic decline and political challenges. The feudal chivalric culture was fading into history whilst being romanticized in popular literature, creating a nostalgic yearning for an idealized past that Cervantes both critiques and sympathizes with. The novel reflects Spain’s complex religious landscape following the Reconquista and during the Inquisition, whilst also capturing the social mobility and uncertainty of a society in flux. Hidalgos (lower nobility) like Don Quijote were particularly affected by economic changes, finding themselves with aristocratic titles but diminishing resources and relevance—a tension that underlies the protagonist’s desire to reclaim a meaningful role through chivalric action, however misguided.

What literary genres is Cervantes responding to?

Don Quijote engages with the popular literary landscape of its time whilst transforming the traditions it inherits. Most explicitly, the novel parodies chivalric romances like Amadís de Gaula, which featured idealized knights performing impossible feats and winning the hearts of noble ladies. However, Cervantes’ approach goes beyond simple mockery to incorporate elements of pastoral romances (particularly in episodes featuring shepherds and rustic settings), picaresque novels (in the earthy realism and social critique), Byzantine romances (in its complex plots and coincidences) and the Italian novella tradition (in its interpolated tales). By synthesizing these diverse influences whilst simultaneously critiquing their conventions, Cervantes created a new form that transcended genre boundaries and established the foundation for the novel as we understand it today.

What should I focus on during a first reading?

During your first encounter with Don Quijote, focus on the evolving relationship between the knight and his squire as the emotional and philosophical core of the work. Pay particular attention to moments where reality and imagination blur, noting how perspective shapes experience for different characters. Observe the novel’s structure and its different narrative levels, including the interpolated tales and the presence of multiple narrators questioning textual authority. Track how the main characters develop over time, especially Sancho’s increasing wisdom and Don Quijote’s moments of lucidity. Notice how books and reading function within the story itself, often as both poison and cure. Finally, appreciate the novel’s varying tones, from broad slapstick comedy to profound meditation on human nature and how Cervantes balances these seemingly contradictory elements.

What are some common essay topics?

Analytical approaches to Don Quijote typically engage with several rich thematic areas that continue to resonate with readers and scholars. The tension between reality and illusion provides fertile ground for examining how perception shapes experience and the power of imagination to transform the ordinary. The novel’s formal innovations make it essential for studying the development of the modern novel, particularly its metafictional aspects and narrative complexity. Character analysis offers opportunities to explore psychological depth and transformation, especially in the parallel journeys of Don Quijote and Sancho Panza. Social criticism appears throughout the text in Cervantes’ treatment of class, religion and Spanish institutions, whilst gender roles and relationships reveal complex attitudes toward masculinity, femininity and power. Finally, the function of humor and parody enables discussion of how comedy serves as both entertainment and philosophical tool.

How does the novel handle questions of authorship?

Don Quijote presents one of literature’s most complex explorations of authorship, creating a labyrinthine system that undermines any single authoritative voice. Cervantes constructs an intricate frame where the primary narrator claims to be editing a translation of an Arabic manuscript by the historian Cide Hamete Benengeli, whose reliability is repeatedly questioned. This layering of authors—including the translator, editor and Cervantes himself—creates distance between the events and their telling, forcing readers to actively interpret rather than passively receive the narrative. Part Two further complicates this by responding to an unauthorized sequel published by Avellaneda, incorporating this real-world literary event into the fiction whilst having characters discuss how they were portrayed in the previous volume. This sophisticated treatment of authorship anticipates postmodern concerns with textuality and authority by several centuries.

What role does madness play in the novel?

Madness in Don Quijote functions as a multifaceted literary device that extends far beyond simple comedy or character trait. Through Don Quijote’s selective insanity—which leaves him articulate and reasonable on subjects outside chivalry—Cervantes explores the permeable boundary between imagination and delusion, suggesting that all reality is partly constructed through our perceptions and beliefs. The protagonist’s madness serves as a mechanism for social critique, allowing Cervantes to challenge conventions and hierarchies by having his character misinterpret them according to an outdated code. Philosophically, Don Quijote’s condition raises questions about whether his noble idealism, though disconnected from reality, might represent a higher wisdom than the self-interested rationality of those around him. The novel ultimately suggests that madness and sanity exist on a continuum where all characters—and perhaps all humans—occupy different positions depending on context.

How does the novel engage with issues of class and social status?

Cervantes offers a nuanced exploration of social hierarchy through characters who simultaneously embody and transcend their class positions. The central relationship between Don Quijote (a poor hidalgo) and Sancho (a peasant farmer) evolves from a conventional master-servant dynamic into a friendship that challenges class boundaries, especially as Sancho demonstrates wisdom that equals or exceeds his social betters. Episodes like Sancho’s governance of Barataria directly examine questions of merit versus birth in determining leadership, with the humble squire’s natural justice contrasted against the educated foolishness of his advisors. Throughout the novel, characters from different social strata interact in ways that highlight both the rigidity and the permeability of class distinctions in early modern Spain. Cervantes particularly focuses on the precarious position of the rural hidalgo class, caught between aristocratic pretensions and economic reality, using Don Quijote’s situation to comment on broader social changes during Spain’s transition from feudalism.

How has Don Quijote influenced later literature?

Don Quijote’s literary influence has been so profound and pervasive that virtually all subsequent novel-writing acknowledges its debt to Cervantes, either directly or indirectly. The development of character-driven narratives with psychological depth can be traced to Cervantes’ pioneering work in creating complex figures who evolve throughout the story. His use of unreliable narrators and metafictional techniques established narrative strategies that would become central to authors from Sterne and Fielding to Borges and Pynchon. The novel’s successful blending of comedy with serious philosophical and social inquiry created a template for works that refuse simple generic classification. Most fundamentally, Cervantes’ exploration of how fiction shapes reality and how individuals construct their identities through narrative anticipates central concerns of modern and postmodern literature, making Don Quijote not just the first modern novel but in many ways still the most contemporary.

Why is the novel still relevant today?

Four centuries after its publication, Don Quijote continues to resonate with readers because it addresses fundamental aspects of human experience that remain remarkably unchanged. The quest for personal identity and meaning in a world that may not accommodate our ideals speaks directly to contemporary concerns about authenticity and purpose. Cervantes’ exploration of how stories shape our perception of reality has only become more relevant in our media-saturated age, where distinguishing between truth and fiction grows increasingly challenging. The novel’s compassionate yet clear-eyed examination of how we balance idealism against pragmatism offers wisdom for navigating our own complex moral landscapes. Its social critique, though specific to early modern Spain, provides a model for questioning institutional authority and conventional wisdom. Perhaps most importantly, Don Quijote affirms the transformative power of imagination whilst acknowledging its potential dangers, capturing the beautiful, tragic and comic aspects of the human capacity for self-invention.