Granada does something no other Spanish city quite manages – it makes you feel like you’ve stumbled into somewhere that shouldn’t exist anymore. Here’s this Moorish palace sitting on a hill, surrounded by Islamic gardens and medieval Arabic quarters, with the Sierra Nevada providing snow-capped backdrop most of the year. It’s the sort of scene that feels digitally enhanced even when you’re standing right there looking at it.

The city’s cleaned itself up since the late ’80s – tourism infrastructure has improved dramatically, and property prices in the old quarters have gone through the roof. But Granada’s retained this edge, this sense that it’s not entirely tamed or packaged for visitors.

What makes Granada distinctive is how the layers sit alongside each other rather than one replacing the previous. The Alhambra dominates visually and historically – it’s unavoidable and genuinely lives up to impossible expectations. But the city’s not just serving as backdrop to its famous palace. There’s proper Andalusian life happening – the tapas culture where drinks still come with free food, the university keeping things youthful and chaotic, the Roma community maintaining flamenco traditions in Sacromonte’s caves, North African communities adding another layer to the Arabic heritage.

The contradictions create energy. You’ve got package tourists queuing for Alhambra tickets whilst locals argue politics over morning coffee, international students learning Spanish in language schools whilst elderly Granadinos speak an Andalusian dialect so thick even other Spaniards struggle with it, pristine tourist areas metres from genuinely rough neighbourhoods that haven’t gentrified yet.

When it comes to things to do in Granada, you’re looking at a city that rewards spending time beyond the obvious headline attraction. Yes, the Alhambra justifies the journey alone – but Granada reveals itself properly when you’ve explored the Arabic quarters, sat through a flamenco performance in a Sacromonte cave, negotiated the tapas bar rituals, and understood why the Sierra Nevada backdrop matters to the city’s character. Here’s what genuinely deserves your attention.

Best Things to Do in Granada

Thirteen attractions might seem ambitious for a city Granada’s size, but the variety justifies it. Some are globally famous – the Alhambra appears on bucket lists whether people can locate Granada on a map or not. Others reveal the city’s distinctive character and cultural complexity beyond that Moorish palace everyone photographs.

The Alhambra

Look, there’s no point being contrarian about the Alhambra – it’s genuinely extraordinary and lives up to expectations that most famous monuments can’t match. Originally a 9th-century fortress, the Nasrid dynasty transformed it during the 13th and 14th centuries into this palace complex that represents Islamic art and architecture at its absolute peak. The name comes from Arabic al-qal’a al-hamra – “the red fortress” – referring to how the walls glow at sunset.

The Nasrid Palaces are what everyone comes for, and rightly so. Those rooms with their impossibly intricate stucco work, the geometric patterns that seem to shift as you move, the Arabic calligraphy flowing across walls and ceilings, the play of light and water through courtyards – it’s architecture as meditation space. The Courtyard of the Lions, with its slender marble columns and central fountain, creates these perspectives that feel deliberately designed to stop you in your tracks.

What strikes me after countless visits is how the spaces work on multiple levels simultaneously. Yes, it’s visually stunning in ways photographs can’t quite capture. But there’s also this mathematical precision to the proportions, symbolic meanings layered into every decorative choice, acoustic properties that were clearly intentional. The Nasrids were showing off – this was propaganda architecture demonstrating cultural sophistication to anyone who visited.

The later additions tell different stories. Charles V’s Renaissance palace sits somewhat awkwardly within the complex – circular courtyard, classical proportions, asserting Christian authority through architectural contrast. Some find it jarring, others appreciate the historical layering. It houses museums that most people skip in their rush to see the Nasrid bits, which is fair enough given limited time.

Practical matters: Alhambra tickets must be booked well ahead, particularly for peak season. The Alhambra limits daily numbers, and they enforce timed entry to the Nasrid Palaces strictly. Miss your slot and you’ve missed it – no exceptions, no matter how compelling your excuse. Book online via the official Alhambra website weeks or months ahead for summer visits, slightly less advance notice works for winter.

Go early if possible – first entry slot means fewer crowds, better light, more space to actually experience the rooms rather than shuffling through in queues. The complex is larger than most people expect – allocate three to four hours minimum, longer if you’re genuinely interested rather than just ticking boxes. Wear comfortable shoes because there’s considerable walking involved, much of it uphill.

The Generalife

The Generalife sits just above the Alhambra – it was the Nasrid rulers’ summer palace, providing escape from court formalities and cooler temperatures during Andalusian summers. The name apparently means “Garden of the Architect”, though Arabic etymology gets disputed by scholars who love arguing about these things.

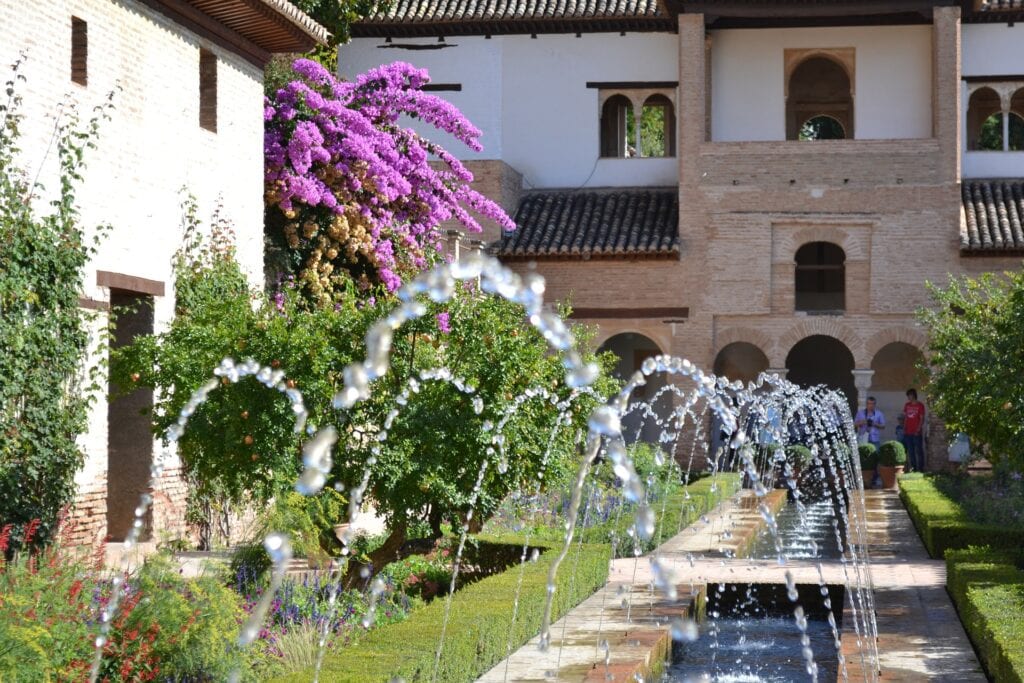

The gardens are the main attraction here, representing Islamic landscape design principles about water, geometry and creating earthly paradise. Those long pools reflecting arcades, the cypress trees providing vertical punctuation, the sound of water constantly present but never overwhelming – it’s landscape architecture that’s survived centuries whilst retaining its essential character.

The Patio de la Acequia epitomises this aesthetic – that elongated pool framed by flowerbeds and pavilions, water jets creating patterns that shift with wind. It’s the sort of space that makes you understand why the Nasrids considered gardens essential rather than decorative.

The views across to the Alhambra and down over Granada provide perspective you don’t get from within the palace complex itself. You see how the whole thing sits in the landscape, how the Sierra Nevada backdrop works, why this particular hillside location mattered strategically and aesthetically.

The Generalife gets included with Alhambra tickets, and most people tack it on at the end of their palace visit. That’s fine, though if you’re genuinely interested in landscape design, allocate proper time rather than rushing through because you’re exhausted after the Nasrid Palaces. Early morning or late afternoon offers best light and fewer tour groups trampling the atmosphere.

The Albaicín

The Albaicín is where Granada’s Islamic character persists most tangibly – this hillside quarter of narrow streets climbing opposite the Alhambra retains its medieval Arabic layout despite centuries of Christian rule. It’s been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984, which brought protection but also the inevitable gentrification and tourist attention.

I remember when the Albaicín was considerably rougher – you didn’t wander certain streets after dark, drug dealing was openly visible, and locals warned you about which areas to avoid. It’s been cleaned up dramatically, which depending on perspective represents either welcome improvement or loss of authentic character. Probably both simultaneously.

The streets don’t follow any logic accessible to modern minds – they twist, dead-end, suddenly open into small squares, climb at angles that leave you breathless, then descend vertiginously. Getting lost is inevitable and largely the point. Those whitewashed houses hide interior patios you glimpse through doorways, jasmine grows over walls creating that distinctive Albaicín scent, and the views toward the Alhambra appear unexpectedly as you round corners.

The neighbourhood’s developed this odd mixture – restored houses converted to boutique hotels or high-end rentals sit alongside family homes that have been there for generations, Moroccan tea houses attract tourists seeking “authentic” experiences whilst locals drink coffee in traditional bars, craft shops selling overpriced jewellery operate next to neighbourhood grocers that haven’t updated stock since the ’70s.

San Nicolás church and its famous mirador (more on that shortly) anchor the upper Albaicín. Lower down toward Plaza Nueva, the atmosphere shifts – more restaurants catering to tourists, language schools attracting international students, the streets slightly wider and more navigable. The whole quarter rewards simply wandering for hours without particular destination, though comfortable shoes aren’t optional given those hills and cobblestones.

Mirador de San Nicolás

Right, this viewpoint in the Albaicín has become Granada’s most photographed spot, and for once the fame is entirely justified. The Alhambra sits across the valley with the Sierra Nevada rising behind it, creating this composition that’s almost absurdly perfect. At sunset when the palace glows golden and the mountains catch pink light, it’s the sort of view that makes even cynical travel writers go quiet momentarily.

Bill Clinton supposedly called it “the most beautiful view in the world” during a 1990s visit, which locals never tire of mentioning. Whether he actually said that or it’s been embellished through repetition isn’t entirely clear, but the view certainly justifies hyperbole.

The square around the viewpoint has become this permanent gathering space – street musicians (quality varies from brilliant guitarists to enthusiastic but limited buskers), artists selling paintings and jewellery, tourists with cameras, young Granadinos drinking beer, elderly residents watching the circus with resigned amusement. It gets absolutely mobbed at sunset during peak season, which rather diminishes the experience of elbowing through crowds to glimpse the view between selfie sticks.

Go at different times if you want actually contemplative experience rather than just documentary evidence you were there. Early morning offers best light and almost nobody else. Midday is harsh light but fewer crowds. Late afternoon builds toward that golden hour but brings the tour groups. Pick your priority.

The area around San Nicolás has restaurants and cafés capitalising on proximity to the viewpoint. Some are decent, others are coasting on location whilst serving mediocre food at inflated prices. If you’re staying in the Albaicín, you’ll pass through regularly and develop opinions about which establishments deserve patronage.

Sacromonte

East of the Albaicín, Sacromonte climbs into hills where the Roma community established itself in cave dwellings centuries ago. The caves – carved into soft rock, whitewashed, surprisingly spacious once you’re inside – became homes, workshops and eventually performance spaces for flamenco.

Sacromonte’s relationship with Granada has always been complicated. The Roma faced (and face) discrimination whilst simultaneously being romanticised for their cultural contributions, particularly flamenco. The caves were poverty housing for generations, gradually being abandoned as residents moved to standard apartments. Then tourism discovered Sacromonte, and suddenly those caves became valuable as performance venues and increasingly as residences once they’ve been properly renovated with electricity, plumbing and structural reinforcement.

The zambra style of flamenco developed here – intimate, intense, closer to the art form’s roots than the polished tablao performances in city centres. Attending a zambra in an actual Sacromonte cave remains one of Granada’s essential experiences, though the authenticity question hovers constantly. Are you witnessing genuine tradition or performance of tradition for tourists? Probably both, and the line between them has always been blurry anyway.

The Sacromonte Abbey sits above the cave district – baroque building housing relics and catacombs connected to Granada’s early Christian martyrs. The views from here across the city and the Alhambra provide different perspectives than San Nicolás, with fewer crowds because most tourists don’t make it this far uphill.

Walking through Sacromonte during day reveals the neighbourhood’s split character – restored caves operating as museums or performance venues, others still functioning as residences, some remaining abandoned and crumbling. It’s gentrifying like everywhere else, though more slowly than the Albaicín. Come evening when performances begin, the whole hillside comes alive with sound.

Granada Cathedral and Royal Chapel

After conquering Granada in 1492, the Catholic Monarchs set about asserting Christian authority through architecture. The cathedral sits on the site of Granada’s main mosque – deliberate symbolism that wasn’t subtle then and isn’t now. Construction began in the early 16th century and dragged on for centuries, which explains the mixture of Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque elements.

The interior is surprisingly light – high vaulted ceilings, enormous windows, white stone creating this airy quality quite different from Spain’s darker Gothic cathedrals. It’s not particularly cosy or mystical, but it certainly makes a statement about power and permanence. The main chapel is massive, the side chapels elaborate, the whole thing designed to impress and perhaps slightly intimidate.

More historically significant is the adjacent Royal Chapel where Ferdinand and Isabella are buried alongside their daughter Joanna and her husband Philip the Handsome. Their marble tombs lie in the main chapel whilst the actual bodies rest in a crypt below – typically elaborate Spanish arrangements around death and memory.

The Royal Chapel also houses their personal art collection – Flemish paintings, religious works, objects of devotion. It’s remarkably intimate given these were Spain’s most powerful monarchs. You get a sense of their aesthetic preferences, religious intensity and the period’s cultural currents in ways that grand monuments don’t quite convey.

Both cathedral and chapel charge separate admission, which feels slightly grasping but reflects how Spanish churches fund themselves. Whether you visit depends on your interest in religious architecture and Spanish history. If you’re saturated with churches after visiting other Spanish cities, it won’t revolutionise your understanding. If you’re interested in how the Reconquista played out architecturally, it’s essential context.

Granada’s Tapas Culture

Here’s where Granada genuinely excels in ways that justify the city’s reputation – the tapas tradition where every drink comes with free food. Not token olives or crisps, but actual substantial tapas that constitute proper snacking or even small meals if you’re hopping between bars strategically.

This isn’t universal across Spain – most cities abandoned free tapas decades ago as tourism increased and margins tightened. Granada’s maintained it through some combination of tradition, competition and student-driven demand for value. The system works simply: order a drink, receive a tapa, eat it, order another drink, receive another (usually different) tapa. The selection varies by bar – some offer choice, others serve whatever they’re making that day.

Quality ranges dramatically. Some bars are genuinely serious about their tapas – changing offerings seasonally, cooking traditional dishes properly, treating the free tapa as point of pride rather than obligation. Others serve depressing processed rubbish that happens to be free. After a few attempts you develop radar for which establishments care and which are going through motions.

The areas around Calle Elvira and Plaza Nueva concentrate tourist-oriented bars where English menus and international crowds dominate. Venture into Realejo or slightly further from the centre and you’ll find places where locals outnumber visitors and the tapas quality improves noticeably. Ask Granadinos for recommendations – they have strong opinions about which bars maintain standards.

The social function matters as much as the food. You’re not sitting for formal meals – you’re standing at bars, chatting with strangers, debating football or politics, moving to the next place when the mood strikes. It’s how Granada conducts significant portions of its social life, and participating provides access to local rhythms you won’t find in formal restaurants or tourist attractions.

Traditional dishes appear regularly: tortilla española (potato omelette), croquetas (bechamel croquettes with various fillings), albóndigas (meatballs in sauce), patatas bravas (fried potatoes with spicy sauce), salt cod preparations, local stews. More inventive bars push boundaries whilst respecting tradition – modern techniques applied to Andalusian ingredients, presentations that elevate bar food without becoming pretentious.

Hammam Al Ándalus

Granada’s Moorish heritage extends beyond monuments into experiences like the hammam – traditional Arab bathhouse. Hammam Al Ándalus near the Darro River occupies atmospheric underground spaces with Moorish-style architecture – horseshoe arches, star-patterned ceilings, dim lighting creating ambience that oscillates between relaxing and slightly stagey. The experience involves moving between pools of varying temperatures, steam room sessions, optional massages, generally spending 90 minutes in enforced tranquillity.

Is it authentic? Not really – the historical hammams served different social and religious functions, involved more vigorous washing rituals, and weren’t primarily about tourist relaxation. But as contemporary wellness experience referencing historical traditions, it works well enough. The environment is genuinely atmospheric, the temperature contrast between pools is pleasant, and the mandatory quiet creates respite from Granada’s intensity.

Book ahead, particularly for evening sessions which are popular. They enforce reservations strictly and won’t accommodate walk-ins when fully booked. The experience isn’t cheap compared to general Granada prices, but reasonable within wellness tourism context. Whether it’s worthwhile depends on your interest in bathhouse culture and how much you need enforced relaxation during your trip.

Science Park (Parque de las Ciencias)

Right, complete tonal shift here – Granada’s Science Park represents the city’s other face, the modern university town rather than the Moorish heritage destination. Located south of the centre, it’s one of Spain’s leading interactive science museums with exhibits covering physics, biology, astronomy, technology and environmental sciences.

The approach is hands-on rather than contemplative – displays you manipulate, experiments you conduct, concepts demonstrated through interaction. Children love it for obvious reasons, though the exhibits engage adults equally if you’re genuinely interested rather than just killing time. The planetarium offers regular shows, the butterfly house maintains tropical conditions and remarkable specimens, and the observation tower provides panoramic city views without the Albaicín’s uphill walking.

For families travelling with children, the Science Park provides necessary contrast to historical sites where “don’t touch anything” becomes exhausting mantra. The kids can run about, engage physically, learn through doing rather than being lectured at. The museum’s thoughtfully designed enough that adults don’t suffer through it – you’re learning alongside the children rather than just supervising.

It’s outside the main tourist circuit, requiring either taxi or bus journey from the centre. That means fewer international visitors and more Spanish families, which creates different atmosphere than you’ll find at the Alhambra or Albaicín. Whether you visit depends on having children along, interest in interactive science museums, or wanting to see Granada’s contemporary side beyond the heritage focus.

Carmen de los Mártires

Granada’s cármenes are distinctive urban gardens attached to houses – typically walled, combining ornamental plantings with productive fruit trees and vegetables, incorporating water features and terraces. The concept descends from Islamic design principles about creating paradise gardens whilst maintaining practical cultivation. The word itself comes from Arabic karm meaning vineyard.

Several cármenes open to visitors, though many remain private properties hidden behind walls throughout the Albaicín and Realejo. Carmen de los Mártires near the Alhambra represents one of the finest accessible examples – extensive gardens combining French landscaping, English romantic elements and Moorish courtyard traditions in this peculiar mixture that somehow works.

The grounds include terraced gardens, a lake with swans, shaded paths through plantings, viewpoints across the city, and that combination of cultivated precision with deliberate wildness that characterises the carmen aesthetic. It’s free to enter, rarely crowded, and provides respite from tourist intensity elsewhere in Granada.

What makes the cármenes significant beyond their individual beauty is what they represent about Granada’s cultural continuity – these gardens maintained Islamic design principles through centuries of Christian rule, adapted them to different aesthetic movements, and persist as living tradition rather than preserved heritage. Visiting one helps understand how cultural influences layer over time rather than simply replacing previous eras.

Flamenco Performances

Granada’s flamenco tradition runs deep, shaped by Roma communities in Sacromonte, Andalusian musical heritage, and that intensity that characterises the city’s cultural expression generally. The zambra style developed here retains closeness to flamenco’s roots – cave settings, intimate audiences, performers who often learned from family traditions rather than conservatories.

Attending flamenco in Granada means choosing between tourist-oriented shows in the centre versus cave performances in Sacromonte. The former offer professional polish, reliable quality, comfortable seating and convenient locations. The latter provide atmospheric settings, variable quality (from transcendent to merely adequate), harder chairs, and the possibility of genuine rather than performed passion.

Sacromonte’s cave venues trade heavily on authenticity claims that deserve skepticism – these are performances for tourists regardless of their historical setting. But the best ones still offer something powerful that polished tablao shows can’t quite match. When it works – when the guitarist finds momentum, the singer channels genuine emotion, the dancer responds with that connection between music and movement that can’t be faked – you understand why flamenco matters as art form beyond folkloric curiosity.

Quality is wildly inconsistent. Some venues maintain standards, others have become conveyor belt operations where performers go through motions for audiences who wouldn’t recognise excellence anyway. Ask locally for recommendations rather than booking whichever tour operator shouts loudest. The university students often know which venues are actually good versus which are just convenient for tourist buses.

Sierra Nevada and Skiing

Granada’s proximity to the Sierra Nevada – literally visible from the city centre most clear days – provides mountain access that’s rare for Spanish cities. In winter, the ski resort operates just 30 kilometres from Granada’s centre, offering the peculiar experience of skiing Europe’s southernmost resort whilst looking across to North Africa on clear days.

The Sierra Nevada resort isn’t competing with Alps or Pyrenees for extent or snow reliability, but it functions perfectly well for accessible winter sports. The altitude helps – some slopes reach over 3,000 metres, extending the season and maintaining decent conditions. Spanish families dominate weekends, international visitors are relatively few, and the infrastructure works without being particularly charming.

Summer transforms the mountains into hiking territory. Spain’s highest peak, Mulhacén at 3,479 metres, attracts serious trekkers, whilst lower elevation routes offer accessible day hikes from Granada. The landscapes shift dramatically with altitude – Mediterranean vegetation giving way to alpine meadows, bare rock at the summits, microclimates creating unexpected diversity.

For most Granada visitors, the Sierra Nevada remains backdrop rather than destination – that white ridge visible from the Alhambra, the snow-capped peaks framing photographs, the mountains lending scale and drama to the setting. But if you’re here for longer stays or seeking contrast to urban tourism, the mountains reward exploration. Tour operators run day trips to the resort in winter and hiking routes in summer if you lack transport.

The Alpujarras

South of the Sierra Nevada, the Alpujarras region spreads across steep valleys – whitewashed villages clinging to hillsides, terraced agriculture following contours, a landscape that looks simultaneously harsh and cultivated. The area developed distinctively – after Granada fell, some Moorish populations retreated here, maintaining Islamic customs longer than elsewhere. Later, hippies discovered the region in the ’60s and ’70s, creating communes that in some cases persist today.

The villages – Pampaneira, Bubión, Capileira form the most accessible cluster – retain Berber architectural influences visible in flat roofs, narrow streets designed for mule traffic, and irrigation systems dating to medieval periods. Chris Stewart’s book Driving Over Lemons romanticised expat life here, bringing international attention that’s transformed the area from remote backwater to destination for second-home buyers and rural tourism.

Day trips from Granada reach the main villages easily – tour operators run routes, or you can drive independently in about 90 minutes. The landscapes are genuinely spectacular – those white villages against green valleys, the mountains rising behind, cultivated terraces demonstrating centuries of agricultural adaptation. The villages offer craft shops (weaving and pottery are local traditions), restaurants serving mountain cuisine, and hiking trails if you’re staying overnight.

The Alpujarras represent complete tonal shift from Granada’s urban intensity – slower pace, rural concerns, communities trying to balance tourism income against maintaining actual functionality. Whether you visit depends on time available and interest in mountain landscapes. If you’re doing Granada quickly, skip it. If you’ve got a week and want variety, the contrast works brilliantly.

Granada’s Festival Calendar

Granada’s festivals reveal layers of identity and historical memory compressed into annual celebrations. Semana Santa (Holy Week) brings those elaborate processions Spanish cities do so intensely – religious brotherhoods carrying heavy pasos (floats with religious sculptures) through streets whilst crowds watch in that peculiar mixture of devotion and theatrical appreciation. Granada’s processions route through the old quarters and climb the Albaicín hills, creating dramatic settings as robed penitents navigate narrow streets by candlelight.

The Corpus Christi festival in June combines Catholic celebration with traditional Andalusian fair – religious processions alongside casetas (temporary structures) serving food and drink, flamenco performances, fairground rides. It’s when Granadinos come out collectively, maintaining traditions whilst adapting them to contemporary social life.

The International Festival of Music and Dance in summer stages performances in venues including the Alhambra and Generalife – classical music, flamenco, contemporary dance, opera. Having the Alhambra as performance backdrop creates unique atmosphere, though tickets for popular events require advance booking.

Día de la Toma on January 2nd commemorates the 1492 conquest with ceremonies and flags flying everywhere. It’s historically fraught – celebrating Christian victory over Islamic Granada doesn’t sit comfortably in contemporary multicultural context, but the date remains significant locally regardless of how you interpret it.

Frequently Asked Questions about Granada

How do I get to Granada?

Granada has a small airport with limited connections – mainly Madrid, Barcelona, and some European budget airline routes. Most international visitors arrive via Málaga Airport (130 km away), which offers far broader connections. Buses from Málaga to Granada take 90 minutes to two hours depending on route and traffic. Trains also connect the cities, though buses are often more convenient. From Madrid, the journey is around four hours by bus or train, with high-speed rail connections improving but not yet matching bus convenience.

Where should I stay in Granada?

The Albaicín offers atmospheric accommodation in renovated houses, many with Alhambra views, though the uphill cobbled streets mean you’re constantly climbing. It’s authentic and beautiful but not particularly convenient. The city centre around the cathedral provides easy access to shopping, restaurants and transport but lacks the old quarter charm. Near the Alhambra is quieter and convenient for palace visits but feels slightly disconnected from urban life. Budget travellers congregate around Calle Elvira and Plaza Nueva where hostels concentrate and tapas bars cluster thickly.

When is the best time to visit Granada?

Spring and autumn offer ideal conditions – comfortable temperatures, good light, festivals without summer crowding. May and September are particularly lovely. Summer gets genuinely hot – 35-40°C isn’t unusual – though Alhambra tickets are easier to obtain and the city’s fully alive. Winter is quiet with cheaper accommodation, and you can combine city sightseeing with Sierra Nevada skiing, though some attractions reduce hours and weather can be genuinely cold despite Andalusia’s reputation.

How many days should I spend in Granada?

Two full days covers the major attractions comfortably – Alhambra and Generalife (which alone requires half a day), wandering the Albaicín and Sacromonte, cathedral, tapas exploration, perhaps a flamenco performance. Three to four days allows more relaxed exploration, time for museums and lesser sights, day trips to the mountains or Alpujarras. A week makes sense if you’re using Granada as a base for broader Andalusian exploration or simply want to absorb the atmosphere without rushing between attractions.

What is Granada known for?

Granada’s famous primarily for the Alhambra – one of Europe’s finest Islamic monuments and Spain’s most visited attraction after Barcelona’s Sagrada Família. Beyond that, the city’s known for preserving unique tapas culture where drinks come with free food, its dramatic setting between the Sierra Nevada mountains and Andalusian plains, the Albaicín’s Moorish quarter and Sacromonte’s cave dwellings, and its role as the last Islamic kingdom in Western Europe before the 1492 Reconquista. The university gives it significant student population, keeping the city younger and livelier than its heritage focus might suggest.

Is Granada worth visiting?

Absolutely, though it offers a different experience from Spain’s other major destinations. It’s more compact than Madrid or Barcelona, more historically layered than coastal resort towns, grittier than Seville whilst sharing Andalusian character. The Alhambra alone justifies the journey – it genuinely is that remarkable. But Granada works best when you’ve spent time beyond the palace, explored the Arabic quarters, engaged with the tapas culture, and understood how the mountain setting shapes the city’s identity. If you’re doing Spain quickly, Granada competes with other destinations for limited time. If you’re exploring Andalusia properly, it’s essential rather than optional.

How far is Granada from Seville?

About 250 kilometres – roughly three hours by car via motorway. Buses take similar time and run frequently throughout the day. The route crosses Andalusian plains that shift between olive groves, agricultural land and increasingly dramatic landscape as you approach Granada’s mountains. Many visitors combine the two cities when exploring Andalusia, which makes sense given their complementary characters – Seville’s baroque Christian grandeur contrasting with Granada’s Moorish heritage.

Final Thoughts

Granada does this remarkable thing where historical layers remain visible simultaneously rather than one era erasing its predecessors. The Moorish heritage sits alongside Christian monuments, student bars operate in medieval buildings, North African immigrants add contemporary dimension to the city’s Arabic connections, and the whole thing functions as actual city rather than heritage theme park.

What I appreciate after decades of bringing groups here is how Granada’s resisted the urge to smooth out its rough edges entirely. Yes, it’s cleaner and more organised than the ’80s version. Tourism infrastructure has improved dramatically, and the Albaicín’s gentrification has brought both benefits and losses. But the city maintains authenticity that’s increasingly rare in major European destinations – locals still outnumber tourists in many areas, traditions function for residents rather than performing for visitors, and you can still find Granada operating on its own terms.

The Alhambra will always dominate – it’s genuinely that extraordinary, and photographs don’t exaggerate its beauty. But when it comes to things to do in Granada beyond the obvious headline attraction, the city reveals surprising depth. The combination of Islamic heritage, mountain setting, university energy, Andalusian character and that distinctive tapas culture creates something you won’t find replicated elsewhere.

Whether you’re here for two days focused on major sights or a week exploring more thoroughly, Granada rewards the time invested. The city’s compact enough to navigate easily whilst being substantial enough to justify extended stays. Just book those Alhambra tickets well ahead, bring comfortable shoes for the Albaicín’s hills, and accept that the Sierra Nevada backdrop will exceed expectations regardless of how many photographs you’ve seen. That’s Granada – meeting high expectations whilst revealing additional layers photographs don’t capture.